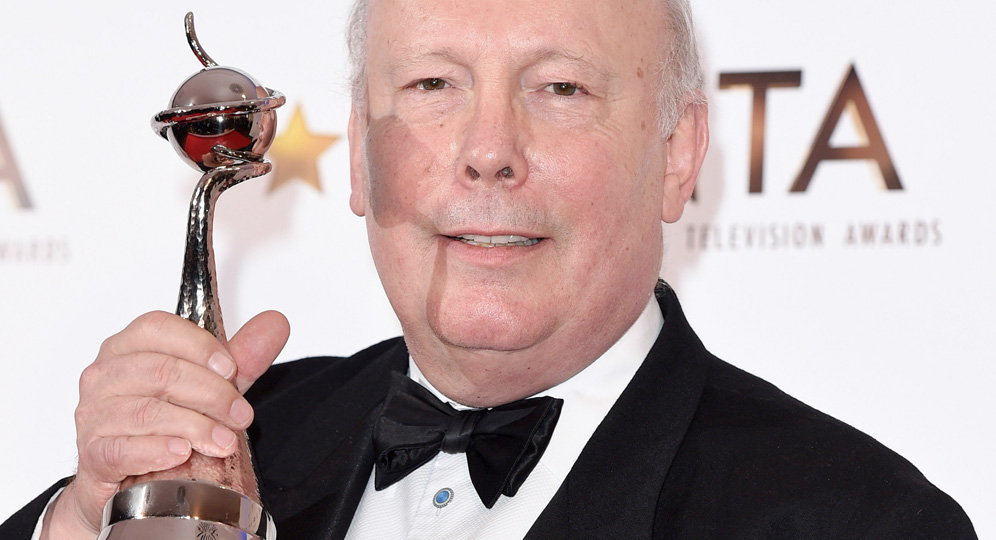

Julian Fellowes

I am a great fan of Anthony Trollope’s and I am happy to proclaim it, even if, like other writers I can think of, he was not highly praised by the intelligentsia of his own day. “Life is vulgar”, said Henry James, “but we know not how vulgar until we see it set down in his pages.” The principal charge against him, according to the received truth at that time, was that he wrote too much which must lead to a lowering of standards. But what really enraged his critics was (and is) the popularity of his work and the enduring audience that his books still reach, a century and a half later. He, himself, was devoid of self‐importance, frequently belittling his achievements and certainly he would strenuously distance the notion that a writer must wait for inspiration. “To me, it would not be more absurd if the shoemaker were to wait for inspiration”. And, risking dismissal as a populist, he definitely liked happy endings. “A novel should give a picture of common life enlivened by humour and sweetened by pathos.” But then, like Anthony Trollope, I like happy endings, too.

I came to him in the standard fashion. The Warden was a set book at school. I liked it enough to read the rest of the Barchester series, but I cannot pretend they set me on fire. It was not until a friend gave me The Eustace Diamonds, with its wonderful anti‐heroine, Lizzie Eustace, that I realized what I was dealing with. Later, The Eustace Diamonds would be one of the first feature film scripts that I wrote and although it was never made (so far at least), it led to Gosford Park and the start of my own Big Adventure. I went on to read the Palliser novels and then progressed to the one‐off books, complete in themselves. I read Ralph the Heir and He Knew He Was Right and The American Senator and I was hooked. I even took Is He Popinjoy? on honeymoon and sat with my nose in it for far more of the time than my wife appreciated.

But perhaps my favourites among them were Doctor Thorne and its semi-sequel, Framley Parsonage, so it will not surprise you that when Christopher Kelly and Ted Childs first approached me with the idea of adapting Doctor Thorne for the small screen, I knew at once I wanted to do it. I was fiercely drawn to the challenge set by Trollope’s ambiguity, to bring his wonderfully modern‐seeming characters, who are neither all good or all bad, to the screen. One of the best examples of these being his immortal creation, Sir Roger Scatcherd (Ian McShane) in Doctor Thorne, where we are encouraged to feel sympathy for the immoral and even criminal perpetrator until we are almost bewildered as to which side we should be on – something Dickens would never have attempted.

Again in Doctor Thorne, we have Lady Arabella Gresham (Rebecca Front), who is first presented as a harsh and unyielding snob but gradually we glimpse her humiliation, her desperation, as her world is crumbling around her, where the folly and failure of her husband and the consequent ruin of her son are making her ill. To place them in a television drama, where the characters must represent themselves, stripped of the all‐knowing novelist’s voice, is always the main task of adaptation and never more than here. Happily we were able to assemble a marvellous cast and good actors can always supply the information that does not come from the dialogue.

Trollope’s view of the world is a merciful one, all‐seeing, all‐understanding and while the people in it may be flawed, they are mainly decent, trying to do their best, trying to play the cards they have been dealt. This, perhaps more than anything else, is why I am such an admirer and why I was so keen to bring Doctor Thorne to a wider audience. He sets out a cast of men and women who are making every effort to live their lives as well as they can, something I am sure is true of most of the human race, and I hope we have brought them faithfully to the screen for you to enjoy.

There is wonderful comedy in Doctor Thorne, the snobbish Countess De Courcy, the waspish Lady Alexandrina, the duped fool, Augusta Gresham, the angry, awkward Mr Moffatt, the archetypal smoothie Mr Gazebee, but there is generosity, too. The worldly Miss Dunstable, the ministering Lady Scatcherd, the remorseful Mr Gresham, are all different incarnations of kindness, and at the centre of them all, Doctor Thorne, himself, played here so brilliantly by Tom Hollander, probably one of the most uncomplicated heroic figures that Trollope ever wrote. But his heroism, if we may so define it, is of the modest and self-‐effacing type. As he says himself, “I have not made my mark in public life. I’ve built no railways. I’ve neither fortune nor title. But I have some skill in saving lives.” And yet, this straightforward man, intelligent and good, touchy and sometimes bad tempered, is fearless when it comes to defending the good name of his niece, and more than generous with those in difficulties, whether the desperate village girl with a bastard child, or the unloved widow of a railway magnate who has lost her way. The story is a testament to Trollope’s belief in decency as a guide to living. We are all made the better for that.