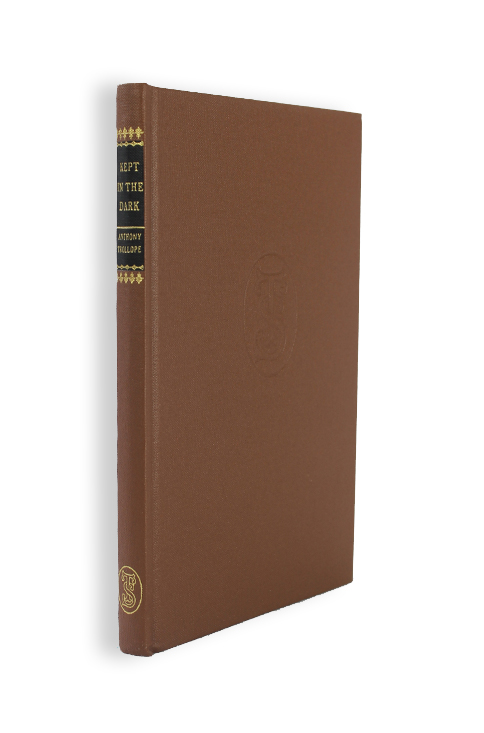

Kept in the Dark

£20.00

Available to members only

Introduction by Derek Parker. Frontispiece by John Everett Millais

176 pages

London, Chatto and Windus, 1882. 2V.

Originally published in Good Words, May-Dec. 1882.

Out of stock

To modern eyes, Kept in the Dark can sometimes seem a very black comedy of manners. George Western meets, and proposes to, Cecilia Holt in Rome, and is quickly accepted. But she conceals from him the fact that she has recently been engaged to the rakish baronet Sir Francis Geraldine, only jilting him when she discovered his true nature. Cecilia keeps these facts in the dark fearing that, since George has himself been recently jilted, her story will only cause him to make unnecessary comparisons.

But her sin of omission — so innocent and well-intentioned at the outset — grows daily larger once she is married, until she finds it almost impossible to confess. Sir Francis, intent on exacting some form of revenge upon Cecilia, writes an odious letter to her husband which reveals everything, and implies worse. George, having idealised his wife as his own unblemished possession, tortures himself with suspicion and jealousy, and leaves her to live abroad. Cecilia — who is by now pregnant — proudly spurns any financial settlement from him, and returns to Exeter to live with her mother.

Neither George nor Cecilia will bend; he considers her tarnished and deceitful, she thinks him cruel and unyielding. Trollope subtly depicts two perfect prigs: George, is curiously unworldly and Cecilia, for all her linguistic skills and literary tastes, is remarkably ignorant. But Trollope surrounds the Westerns with characters who are much funnier, more human, and therefore more lifelike than his two protagonists. Chief amongst these are the dastardly Sir Francis, incapable of letting the slightest affront to his pride go unrevenged; Dick Ross, Sir Francis’ penniless sidekick, who nonetheless speaks his mind over his patron’s wanton cruelty; Lady Grant, George’s wise sister, the only character capable of grasping the truth amidst the supposition and innuendo; and Francesca Altofiore, the novel’s one notable achievement. Descended — as she frequently reminds us — from ‘the Fiascos and Disgracias of Rome’, thirty-five years old, a champion of a woman’s right to remain single (due to her own circumstances rather than any deeply-held conviction), the selfish Francesca causes as much mischief as she can for Cecilia. Her vulgar attempts to ensnare Sir Francis for herself are beautifully written vignettes of coquetry.

Trollope, in the twilight of his career and having recently moved to North End, near Petersfield, here succeeded in writing a dark and slyly comic counterpoint to his other novel about morbid jealousy, He Knew He Was Right. He also achieved a quiet insight into the infinite jealousies of which human minds are capable when they are set — or set themselves — adrift.